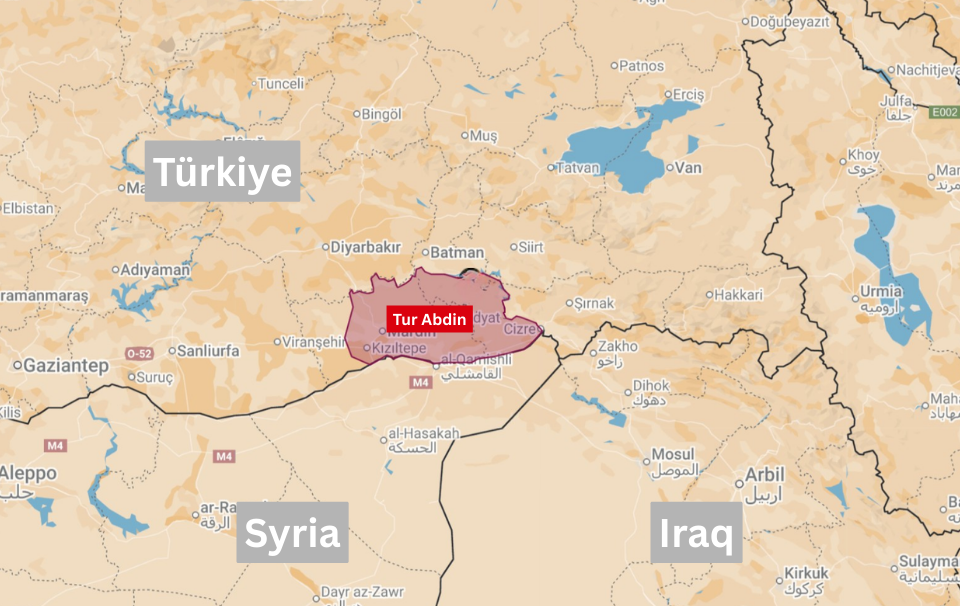

Our parents and grandparents left Tur Abdin in southeast Türkiye during the 1970s, 80s, and 90s. They did not leave in search of comfort or opportunity abroad. They left because life had become uncertain, because pressure was mounting, and because they no longer felt secure about their future. Leaving behind their homes, vineyards, fields, and orchards – lands that had sustained their families for generations. Few believed the departure would be permanent. Most believed that one day conditions would change and that the door would still be open for return.

Decades later, we are confronting a reality that few could have imagined. During the cadastral and land registration processes carried out in the 2000s, vast areas of land in historically Assyrian villages were reclassified as state property by Türkiye and registered as treasury land, forest land, or pasture. These changes did not concern just a few scattered plots. They affected entire landscapes.

For example, in the village of Inwardo (Gülgöze), more than 32 million square meters, equaling around 4 500 football fields, were transferred into state ownership. In Hah (Anıtlı), the figure exceeds 28 million square meters. In Mzizah (Doğançay), nearly 50 million square meters have likewise been registered under state ownership. The same issue exists throughout all our villages in Tur Abdin.

These are not marginal adjustments. They are enormous territories. This land once formed the agricultural and economic backbone of entire communities.

These registrations took place during a period when most of the Assyrian/Syriac population had already migrated and was living abroad. Many families were no longer physically present to monitor, challenge, or even fully comprehend the administrative processes unfolding in their absence.

Today, as more Assyrians/Syriacs visit their villages, restore homes, and consider long-term investment or return, they encounter a legal reality that is difficult to ignore. Land that had been cultivated and regarded as family property for centuries is no longer registered in their names.

Without secure property rights, there can be no meaningful return. No community can build a sustainable future on uncertain legal grounds. Investment becomes risky. Development becomes complicated. Long-term planning becomes fragile. What begins as an administrative reclassification gradually evolves into a structural transformation of ownership and control.

Due to the importance and urgency of this issue, over the past year and a half we have systematically mapped these changes in the land registry. Based on the data we have gathered and documented, the figures are no longer speculative; they are verified. The issue is no longer about identifying the problem. It has been identified. The question now is whether there is political will to address it and resolve it through action by the Turkish authorities.

When tens of millions of square meters in individual villages have shifted into state ownership, this cannot be resolved through isolated court cases pursued by individual families. The scale of the matter exceeds individual litigation. It requires a political framework and a structured review. It requires recognition that many of these registrations occurred during a period when a large part of the indigenous population was effectively absent. It requires a solution that is transparent, lawful, and fair.

If this situation remains unaddressed, the long-term consequences will not be abstract. They will be tangible, and they will affect the very existence of our people in our homeland. Our presence in Tur Abdin will become symbolic rather than structural. We may continue to visit, to celebrate, and to remember, but without territorial and legal anchoring, our ability to remain a living, rooted community in the region will steadily erode. This would be catastrophic for Assyrians/Syriacs, but it is equally bad for Türkiye's long-term stability and interest.

Beyond its historical dimension, this issue also carries strategic importance for Türkiye. A stronger Assyrian/Syriac presence in Tur Abdin would contribute to demographic balance, local stability, and long-term regional resilience in a sensitive border area. Encouraging lawful return, property security, and investment from the Assyrian/Syriac diaspora would stimulate economic development and strengthen social cohesion in the region.

The Assyrian/Syriac diaspora community also serves as a natural bridge between Türkiye and western societies. Policies that reinforce trust, diversity, and inclusion would enhance Türkiye’s international standing while contributing to national stability. A stable and vibrant Tur Abdin is not only in the interest of Assyrian/Syriacs, it aligns with Türkiye’s long-term strategic interests as well.

Our parents left believing that one day they or their children could return to something that still belonged to them. That belief sustained generations in the diaspora. The question now is whether that possibility is being quietly narrowed through administrative procedures.

The documentation exists. The numbers are known. The scale is clear. What remains is the political decision of the Turkish authorities to act.

Without that, we risk becoming strangers on land that once defined who we are.

The time for a political solution is not in the future. It is urgent. It is now.