Much discussion within Assyrian political circles revolves around the “implementation” of Article 125 of the Iraqi Constitution. Yet this debate misses a more fundamental issue. Our problem in Iraq, and equally under Kurdish regional authority, is not merely whether certain constitutional provisions are implemented. The problem lies in the constitutional structure itself.

From its very beginning, the Constitution establishes a hierarchy that marginalizes non-Muslims. Article 2 declares Islam as “the official religion of the State and a foundational source of legislation,” further stipulating that no law may contradict the established provisions of Islam. For Assyrians — an indigenous Christian people whose existence in the region predates Islam by millennia — this framework does not reflect equality. It establishes limitations from the outset.

Article 4 compounds this imbalance by designating only Arabic and Kurdish as the official languages of the state. While other languages may be acknowledged locally, the constitutional hierarchy of language mirrors a hierarchy of power. For an indigenous nation such as the Assyrians, whose language is a direct continuation of ancient Assyria, this relegation is not symbolic — it is structural marginalization embedded in the foundation of the state.

By the time one reaches Article 125, the damage has already been done.

Article 125 speaks vaguely of guaranteeing “administrative, political, cultural, and educational rights” for various nationalities, including Assyrians. Yet what is presented as protection is, in reality, confinement. Why must Assyrians be granted “administrative and cultural rights” as special provisions, rather than recognized as a people entitled to full political equality and national recognition?

Article 14 of the Constitution already affirms equality before the law for all Iraqis. If equality truly exists, why is a separate clause required to guarantee limited administrative and cultural space? The very framing of Article 125 reduces Assyrians to a managed minority within a structure that does not recognize them as a people with inherent national rights.

The ongoing effort by some Assyrian parties and individuals to “implement Article 125” assumes that the constitutional framework is just and merely awaiting activation. But if the architecture itself positions Assyrians as secondary actors within their ancestral homeland, then implementation becomes institutionalization of subordination.

The issue is not enforcement. The issue is design.

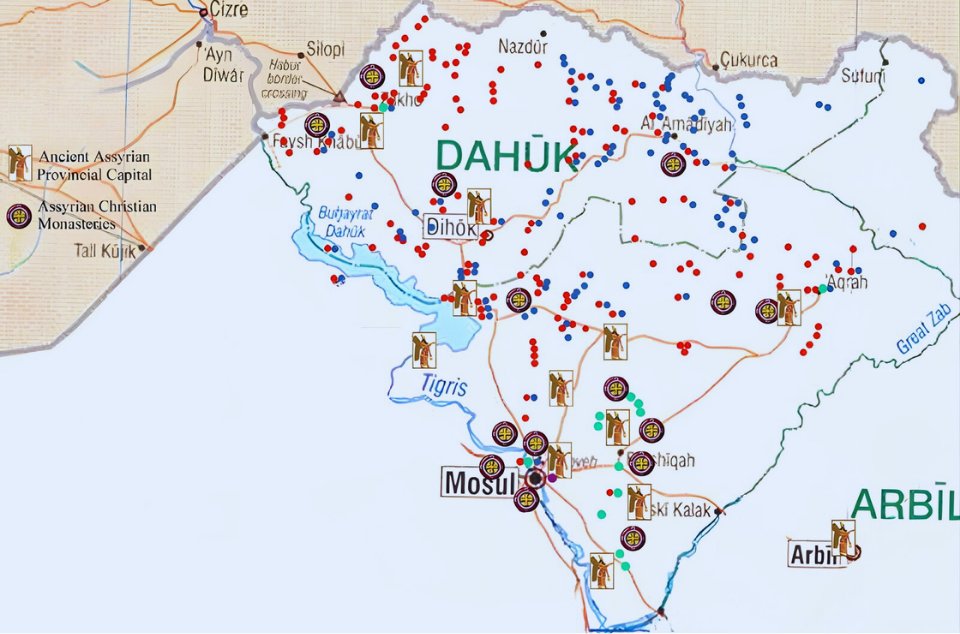

The situation is further complicated in the Kurdish-controlled region, much of which encompasses historically Assyrian lands from which Assyrians were displaced, dispossessed, or administratively absorbed. The Kurdish people have secured federal recognition and constitutional status. The Assyrians — the indigenous people of northern Iraq — remain without equivalent territorial guarantees or federal recognition. This disparity is not accidental. It reflects political realities embedded within the constitutional order itself.

If Assyrians are serious about advocating for meaningful change within Iraq, then the demand should not be reduced to the implementation of vague minority clauses. It should be equality — the same political recognition afforded to the Kurds. Especially when much of the Kurdish region itself has been built upon occupied Assyrian land. If federal status was attainable for one people, it must be attainable for the indigenous people whose land made that autonomy possible.

If Assyrians are to demand anything, it should be the restoration of their occupied lands — a process that continues even as these words are written, most recently in the villages of Bakhetmi and Shiyoz.

This is not a question of cultural recognition. It is a question of political equality, land security, and national dignity.

The Responsibility of the Diaspora

Assyrians in the diaspora must understand something essential: unlike our people living under occupation in Assyria, we are not constrained by fear, party control, economic coercion, or the daily vulnerabilities imposed on those struggling to survive. We are not bound by the same pressures.

We live in societies that shape global policy. We reside in countries that influence international institutions, determine foreign aid, and decide which struggles are heard and which are ignored. We live where power resides — where governments fall, leaders rise, and geopolitical direction is set. With that position comes responsibility.

Yet too often, diaspora Assyrians mirror the language of subjugation instead of challenging it. We debate implementation of flawed provisions rather than confronting the system that marginalizes us. We soften our demands in the name of “realism,” forgetting that realism without dignity becomes surrender.

Our brothers and sisters in occupied Assyria may be forced to negotiate survival. We are not.

If those living freely abroad adopt the same cautious posture as those living under structural constraint, then we voluntarily extend the occupation into our own thinking. That is how nations disappear — not through conquest alone, but through acceptance.

The diaspora must strengthen its message, not dilute it. We must move beyond appeals for cultural recognition and toward firm demands for political equality, indigenous rights, land protection, and self-determination.

Silence is not neutrality. Moderation in the face of erasure is complicity.

If we fail to assert ourselves while we possess freedom of speech, mobility, and institutional access, then future generations will inherit nothing but memory.

A Call for Clarity and Self-Determination

Continued reliance on vague constitutional promises without structural reform risks normalizing diminished status. A nation that accepts perpetual marginal accommodation will eventually dissolve into it.

In a world where geopolitical boundaries shift, alliances evolve, and historical injustices are increasingly revisited, the Assyrian question cannot remain confined to administrative language. The issue is not charity, nor token representation. It is the right to exist securely and equally in our homeland.

Self-determination is no longer a theoretical aspiration — it is our only viable option.

An Assyrian Region, protected by Assyrians and governed for Assyrians, is not an extreme demand. It is the minimum requirement for survival. Every nation understands that security and dignity require political control over one’s own land. Only Assyrians are told to accept permanent vulnerability as realism.

We cannot continue placing our future in a failed constitutional system that has consistently marginalized us. We cannot repeat the same political strategies decade after decade and expect different results. History does not reward patience in the face of erasure.

The time has come for clarity.

Can we finally articulate a coherent national position rooted in self-respect rather than fear? Can we demand equality not as a favor, but as a right? Can we acknowledge that survival requires structural change, not administrative accommodation?

History has shown that nations do not disappear because they are small. They disappear when they accept definitions imposed upon them.

The question before us is no longer whether Article 125 should be implemented. The question is whether we are prepared to assert our right to self-determination — and to build a future secured by Assyrians, for Assyrians, in Assyria.